Elections are currently underway for the council of the European Association for Theoretical Computer Science (EATCS). The EATCS plays a pivotal role in organizing conferences and shaping policy within the field. Its flagship event, ICALP, is widely regarded as the premier European conference in theoretical computer science, and the association also supports a range of other meetings such as DISC and ESA.

At present, the EATCS does not have any policy addressing climate change. Moreover, publishing at ICALP currently requires an in-person presentation, which excludes climate-conscious researchers who are limiting their travel. Among the 24 candidates, 16 mention climate change in some form as a topic relevant to the EATCS. In this blog, we give a high-level overview of the candidates' statements on the matter. Please note that the nuanced positions of each candidate may not be fully captured here; we encourage readers to consult the original statements for a complete picture.

Voting can be done here and closes October 31st. There are 24 candidates this year (listed with their position statements at the end of the post), of which 9 will be elected to join the council. Each EATCS member can vote for up to 5 candidates. You can check whether you are an EATCS member by logging in/resetting your account here or contacting the secretary at secretary<REMOVETHIS>@eatcs.org.

TCS4F Supporters

First, we remark that 10 of the 24 candidates are in fact supporters of the TCS4F manifesto:

- Manuel Bodirsky

- Thomas Colcombet

- Johannes Fischer

- Marcin Jurdzinski

- Denis Kuperberg

- Yannic Maus

- Yasamin Nazari

- Jakub Oprsal

- Jukka Suomela

- Thomas Zeume

Of course, there is a difference between personal behavior and EATCS policy, and neither is this an exhaustive list of the candidates that care about the climate. So let's have a look at the election statements of the candidates. The main topics in their statements are:

- mandatory attendance;

- selecting conference locations wisely;

- co-locating different events;

- incentivizing train travel; and

- incentivizing combining conferences with research visits.

Mandatory Attendance

The most impactful for the climate, is 1) changing the rule that publishing at conferences like ICALP require in-person attendance (see this column and the calculations in this report). Six candidates explicitly mention that we need to reconsider mandatory attendance policies:

- Manuel Bodirsky

- Javier Esparza

- Daniele Gorla

- Denis Kuperberg

- Yannic Maus

- Yasamin Nazari

Candidates mentioning the climate crisis

Lastly, let me give a complete list of all candidates. Using the numbers from above, I show which climate policy they mention in their statements (if any) and whether they signed the TCS4F manifesto. Of course, a candidate that does not mention a certain policy is not necessarily against it. Personally, I do believe that candidates that list a specific measure are more likely to initiate action to make the idea a reality.

- Alkida Balliu (2, 4, 5)

- Petra Berenbrink

- Manuel Bodirsky (1, TCS4F)

- Thomas Colcombet (TCS4F)

- Javier Esparza (1)

- Panagiota Fatourou

- Paolo Ferragina

- Johannes Fischer (TCS4F)

- Pawel Gawrychowski

- Daniele Gorla (1)

- Thore Husfeldt

- Marcin Jurdzinski (TCS4F)

- Jan Kretinsky

- Denis Kuperberg (1, TCS4F)

- Kasper Green Larsen

- Nutan Limaye

- Meena Mahajan

- Yannic Maus (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, TCS4F)

- Yasamin Nazari (1, 2, TCS4F)

- Jakub Oprsal (TCS4F)

- Eva Rotenberg (3)

- Laura Sanita (2, 3)

- Jukka Suomela (2, TCS4F)

- Thomas Zeume (TCS4F)

Written by: Tijn de Vos, Antoine Amarilli

The TCS4F initiative now proposes the tool "Low-CO2 research papers", a way to include on your research papers a logo and statement advertising that the paper was prepared and disseminated with a limited carbon footprint (in particular without the use of air travel).

See here to download the resources and the LaTeX package to use it on your papers, and see the page for more information about the tool, how and when to use it, etc.

This post is to relay some news from SIGACT, in which TCS4F member Tijn de Vos was involved.

Last year, Laurent Feuilloley and Tijn de Vos did some research in the

environmental impact of conference travel. They were invited by Dan

Alistarh to publish our findings in a column in SIGACT news, which is also available on Tijn's website. They compute what impact the location of a conference has on the total

emissions and discuss several more environmentally friendly

alternatives. Although their work focuses on the distributed computing

community within computer science, we think it's worth a read for any

academic.

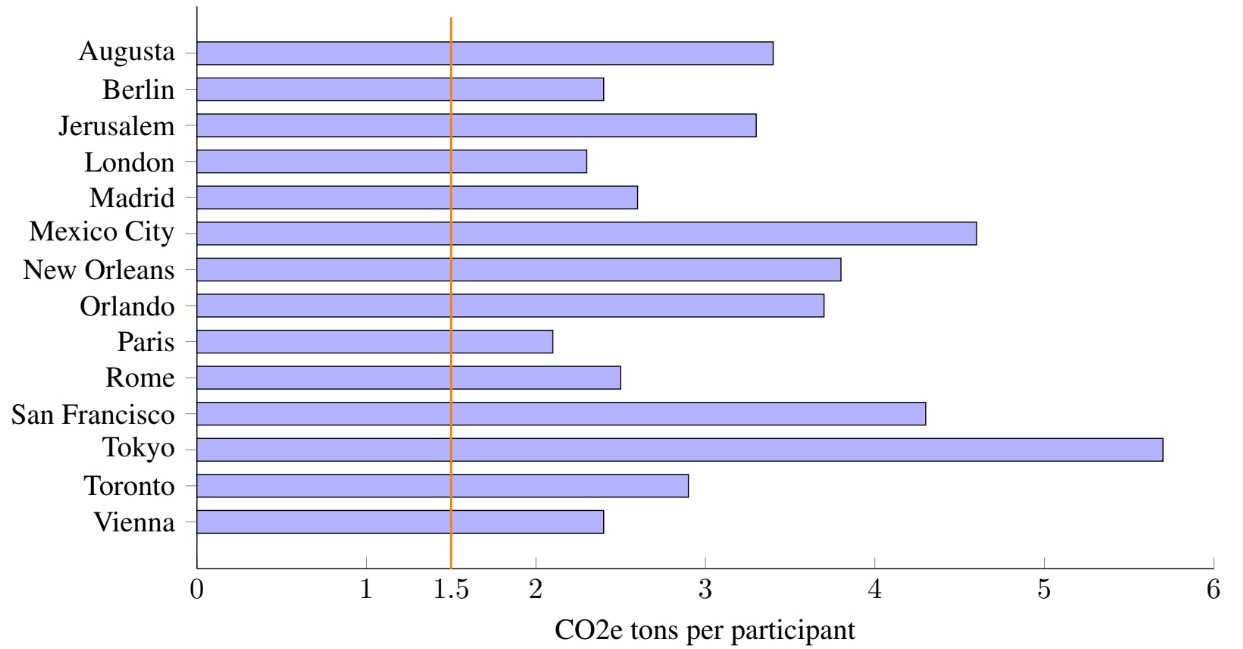

To comply with the Paris Agreement, each person has roughly a CO2

budget of 1.5 tons/year. For the distributed computing community, you

can see in the image below the average CO2 emissions per participant when traveling to a conference, for various locations

around the world. As even the minimum is exceeding

the 1.5 tons budget, it is evident that we need a more structural

change.

The

SIGACT news column gives suggestions of how to mitigate this, and an estimate of their impact.

As COP28 is currently taking place in the United Arab Emirates, we relay the open call of Scientist rebellion. Over a thousand scientists, including some TCS4F members, are warning the world about the impending climate disaster and the dire insufficiency of political action over the last 30 years. This letter has just been covered in the Guardian, and it is still possible to sign it.

As a pledger to the TCS4F manifesto, I try to limit the amount of flying I do for professional reasons. As a PhD student, making new connections is important to me. In the last few years, I've tried to attend important conferences whenever they were a train journey away - also when I did not have a paper there. This led to many good experiences, since train travel within Europe is easy and comfortable.

However, to get your papers published at a conference, the sad truth is that almost all conferences still require in person attendance. Last summer, I had two brief announcements accepted at the Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), held as part of the Federated Computing Research Conference (FCRC) 2023 in Orlando. The FCRC is a mega event, where multiple computer science conferences come together, including for example STOC. It would definitely be interesting to attend, would it no be for the fact that I live in Salzburg (Austria), so it's kind of tricky to get there without flying. So although I was happy that my work was accepted, I was reluctant to travel there. After contacting the chair of the Organizing Committee, the Steering Committee, and the Program Committee, I received a definite "No" on remote presentations/videos for the sake of our climate. I gave in and started to plan my trip.

PODC 2023 took place in the third week of June. Earlier that month, June 6 till 9, I was going to attend the International Colloquium on Structural Information and Communication Complexity (SIROCCO) 2023, held in Alcalá de Henares near Madrid (Spain). The reason to go there was that I had a single-author paper at SIROCCO, and they have a mandatory in-person presentation policy as well. I decided to link both trips to minimize my travel. Here's the story of how I attended, two conferences, one workshop, and visited two non-academic friends along the way. This took place in a little over two weeks, spanning 5 cities in two continents. And all of that with only two flights. And not two "trips including flying", but two direct flights. Oh, and a lot of trains. That is 13 trains with a total of more than 5000 km of train tracks.

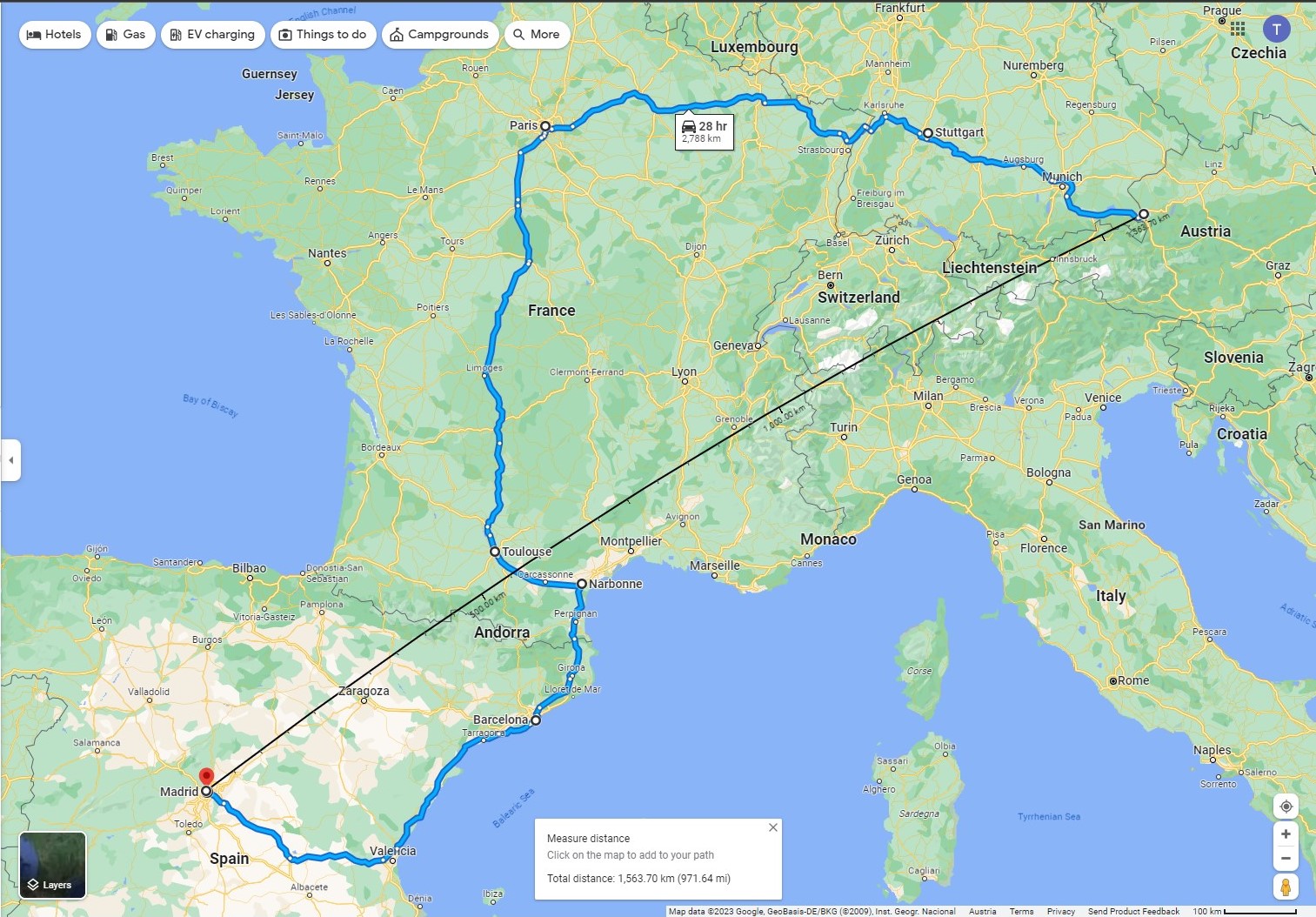

Getting to Spain

The first leg of my journey would be travelling to Madrid. I'd visit a friend there the weekend before SIROCCO. Madrid - Salzburg is only 1500 km apart in a straight line, but this line crosses the Alps and the Pyrenees. The fastest train line is almost twice as long, going over Paris. Perhaps a shorter train connection exists, but it wouldn't be faster. Besides, taking dozens of slowly moving mountain trains did not sound very appealing. I opted for the long high-speed route, which takes roughly 36 hours, including transfer times.

This 36 hours might sound daunting at first, but let me split it out for you. On Thursday morning I took the train from Salzburg to Paris. In the train I finished a review that was almost due, making the hours well spent. For who knows Paris: if you need to transfer in Paris, you also need to change train stations. This is usually a very short metro ride, but I took the opportunity to stretch my legs. I took the 30 minute-walk to my favorite vegan restaurant in Paris: Veget’halles. After enjoying a nice dinner there, I walked another 30 minutes to the next train station. From there I took a night train to Toulouse. One of the advantages of night trains is that you arrive rested at the next city, often even after having had breakfast in the train.

Since I had a long transfer (5 hours) in Toulouse, I took another break from trains and stations. For who knows me, it’s not hard to guess where I went. I spend the morning bouldering at bouldering gym Arkose. After a good workout and a shower, I headed towards the city for some lunch at a Chinese restaurant. The afternoon was – of course – spent in trains again. After transfers in Narbonne and Barcelona, I was in my final train to Madrid. I can especially recommend the Narbonne-Barcelona train. This one has beautiful views of the countryside, parts of the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean. I’d say there are worse places to work on your conference presentations. On the topic of working on the train: most European trains have good Wi-Fi nowadays. Even videocalls aren’t out of the question. However, this is hard to estimate if you haven’t taken a particular train before. I always make sure to have offline options, such as printed papers to read and LaTeX running on my computer rather than Overleaf. And as we all experience sometimes: being offline is often more productive than when you have access to the distractions of the internet.

Train travel in the USA

I was very lucky that there was exactly a workshop on graph algorithms hosted at Rutgers University in the week between my two conferences. The program was almost exactly my research field, I was eager to hear from some of the speakers, and it gave me the oppurtunity to meet up with some of my collaborators that live in other countries. To get there, I took a direct flight to New York. After the workshop, I took the two hour train to Washington DC, where I got to spend the weekend with another friend. The next train, from Washington DC to Orlando had a special feel to it. Most Americans do not even realize this 20-hour train ride is an option, and book a flight right away. The train ride is also unfortunately much more expensive. Luckily, my university (the university of Salzburg) has the policy that you can always take a train, and if the journey is more than 8 hours, you can book a private cabin. (In fact, the university of Salzburg does not fund short-haul flights at all anymore.) This made my east coast trip a comfortable ride, where the private cabin is ideal for getting some work done. My train did not have Wi-Fi, and being disconnected can have the benefit of getting some productive hours in. In this case, I spend some time reading papers and working on my slides.

Getting back home

For my way back from Orlando, I could choose to fly to Salzburg via Frankfurt, or fly only to Frankfurt and take the train from there. For some capitalistic reason, the two flights were roughly 100 euros cheaper than taking only the first. Environmentally speaking, it is of course better to travel by train when you can. I chose this option, given the luxury that my supervisor’s grants can cover this and it is in line with my university’s travel policy. A big benefit is here that you can book a flexible train ticket; due to weather conditions the flight from Orlando to Frankfurt was somewhat delayed. That meant that some of my colleagues on the same flight missed their connection, delaying them by several hours. For me this was no issue, I walked straight out of the plane into the next train.

CO2 comparison

To see what all this effort led to, let's do a rough comparison in emissions. The more conventional way of doing this journey would be flying Salzburg-Madrid, Madrid-New York, New York-Orlando, Orlando-Salzburg. I won't go into details here, but in the CO2 emissions are roughly: Salzburg-Madrid: 444, Madrid-New York: 1467, New York-Orlando: 419 Orlando-Frankfurt: 2363, and Frankfurt-Salzburg: 113 kg CO2. This adds up to 4806 kg CO2. If I replace the three unnecessary flights (total 976 kg) by train rides (total 150 kg), the total becomes 3979 kg CO2. Remember that we have 1500 kg CO2/person/year (see for example

here). My personal conclusion from these sort of numbers is that you can travel as much by train as you want, while flying to another continent is something that can only be done every few years – definitely not a few times per year.

Final reflections

Although taking the train takes significantly more time, it is a more comfortable way of traveling – in my opinion. Moreover, the long travel times force you to rethink if the travel is actually necessary. Cutting unnecessary travel might be the biggest win for the climate in the end.

On a bit of a side note, let me say that CO2 compensation schemes are not a valid alternative. Instead of me trying to explain this, I’ll refer to

this Guardian article.

This journey has been undertaken within research projects receiving funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (P 32863-N) and by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 947702).